For decades, prenatal vitamins have been available and recommended by providers. Pregnancy is a time of intense physiological change both for mother and baby, and appropriate supplementation of various vitamins and minerals is needed. But now there’s something new on the market – postnatal vitamins!

Postnatal vitamin and mineral supplements (which we will call “postnatal supplements” hereafter) have recently been introduced for breastfeeding women. As in pregnancy, adequate nutrition during the postpartum period is crucial to ensure optimal health of mother and baby. Breastfeeding mothers are both recovering from their pregnancy and delivery and producing milk for their newborn – two incredibly demanding physiological processes. Breast milk provides complete nutrition for an infant, and is composed of protein, lipids, carbohydrates, and all essential vitamins and minerals. Ideally, breastfeeding mothers should obtain most of their required vitamins and minerals by consuming a balanced, varied, and nutritious diet. However, mothers may benefit from supplementation of some of the various components that are secreted into their breastmilk. There are several factors that lactating mothers should be aware of before deciding if postnatal supplements are right for them.

Nutrient Requirements during Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

The nutritional requirements of some key essential nutrients for pregnant and lactating women are outlined below.

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is needed for vision, immune function and proper cellular differentiation and signaling.1 The recommended dietary intake of Vitamin A for lactating women ages 19-50 is 1300 mcg, which is substantially higher than the recommended intake for pregnant women which is 770 mcg.2 This is to compensate for the relatively high amount of Vitamin A that is secreted into breast milk.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is an important antioxidant.3 The recommended dietary allowance for Vitamin E for lactating women ages 14-50 is 19 mg, as compared to 15 mg for pregnant women.2 Similar to Vitamin A, this increased requirement is to compensate for the Vitamin E that is secreted into breast milk.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that is necessary for proper absorption of calcium and bone mineralization. Breast milk contains inadequate levels of Vitamin D and all infants require supplementation to ensure proper bone mineralization. This is particularly important for women with dark skin, those who live in locations with little sunlight, and those with a diagnosed Vitamin D deficiency. The concentration of Vitamin D in breast milk does not respond proportionally to increased maternal intake, and there is conflicting evidence of the effects of maternal supplementation on Vitamin D levels in breast-fed infants.4 Some research has reported that very large maternal doses of vitamin D that exceed the safe upper limit of 4000 IU per day can provide adequate vitamin D to the infant through breast milk.5 However, caution is warranted on consuming these large doses, as excess intake can cause toxicity. Currently, the recommended dietary allowance for Vitamin D for is the same for women who are pregnant or lactating as it is for non-pregnant/non-lactating at 600 IU, or 15 mcg.2

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is necessary to facilitate proper blood clotting. Similar to Vitamin D, breast milk contains inadequate levels of Vitamin K for infants. Thus, all newborns are given a Vitamin K injection at birth to prevent hemorrhage. Breastfeeding mothers do not require additional supplementation of Vitamin K — the recommended dietary amount for both lactating and pregnant women ages 19-50 is 90 mcg.2

Vitamin C

Vitamin C is responsible for synthesizing collagen and is necessary for proper wound healing.6 Vitamin C is also secreted in breast milk — thus, a higher dietary intake is recommended for lactating women to make up for this loss. The recommended dietary amount for lactating women ages 19-50 is 120 mg and pregnant women is 85 mg.2

Calcium

The recommended daily intake of calcium is the same for lactating mothers as it is for pregnant and non-pregnant women at 1000 mg.2 During pregnancy, calcium availability in the body increases through increased absorption of calcium from foods, increased mobilization from bones, and decreased calcium loss through the kidneys. These changes are sustained during lactation. Increased mobilization of calcium from bones results in temporary bone loss during pregnancy and lactation, however, this loss is recovered once lactation ceases.7

Iron

The recommended dietary amount of iron for lactating women ages 19-50 is 9 mg, which is less than the recommended amount for pregnant women (27 mg), and nonpregnant women (18mg).2 This is due to lactational amenorrhea, the temporary period in which a postpartum woman is breastfeeding and not menstruating, thus reducing her iron loss. For women who experience excessive blood loss during delivery or postpartum hemorrhage, iron-deficiency anemia during the postpartum period is extremely common. Oral iron supplementation during the postpartum period can help recover these losses and restore iron stores.8 Mothers who have had excessive blood loss should talk to their provider about assessing iron status (checking serum ferritin levels) at their postpartum visit.

Iodine

Iodine is a mineral that is necessary for proper production of thyroid hormone, which is crucial for brain development in the developing fetus. The recommended dietary amount of Iodine for lactating women is 290 mcg, which is higher than the recommended amount for pregnant women (220 mcg), and nonpregnant women preparing for pregnancy (150 mcg).2

Folate

The neural tube is the embryological precursor to the central nervous system, which is composed of the brain and spinal cord. The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends supplementing folic acid daily even prior to conceiving in order to reduce the potential for a fetal neural tube defect.9 The recommended dietary amount of folate for lactating women is 500 mcg, whereas the recommended amount for pregnant women is 600 mcg.2

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 plays an important role in an infants’ neurological development. Infants of lactating mothers who are deficient in Vitamin B12 may develop anemia or exhibit neurological abnormalities.4 Vitamin B12 levels are reduced in the breast milk of mothers who follow vegan diets or other restrictive diets that exclude meat, chicken, fish or dairy. Similarly, Vitamin B12 levels can be reduced in mothers with pernicious anemia, an autoimmune disorder that limits Vitamin B12 absorption, and mothers who have undergone gastric bypass surgery. For women with these unique needs, it is particularly important to supplement Vitamin B12 while lactating. There is a scarcity of research on the effects of oral supplementation of Vitamin B12 during lactation, however the recommended dietary amount of Vitamin B12 for lactating women is 2.8 mcg.2

Zinc

The recommended dietary allowance of zinc in lactating women is 12 mg, and 11 mg in pregnant women.2 This is to compensate for the zinc that is secreted in breast milk.

Selenium

The recommended dietary allowance of selenium in lactating women is 70 mcg, and 60 mcg in pregnant women. This is to compensate for the selenium that is secreted in breast milk.

Omega-3

Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), particularly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are important for proper development of the brain and retina.10 Maternal intake of omega-3 LCPUFA through fish consumption has been shown to increase the concentrations of omega-3 LCPUFA in breast milk.11 However, certain species that are likely to have high levels of mercury should be avoided, as these are harmful to the developing nervous system.12 Currently, there is not enough research on omega-3 supplementation while breastfeeding and its subsequent effect on infant cognitive development. The recommended dietary allowance of omega-3 LCPUFA in breastfeeding women is 200 mg daily, or 8-12 ounces of seafood weekly that are low in mercury levels (catfish, salmon, shrimp, tilapia).2

Nutrient Breakdown for Common Postnatal Supplements

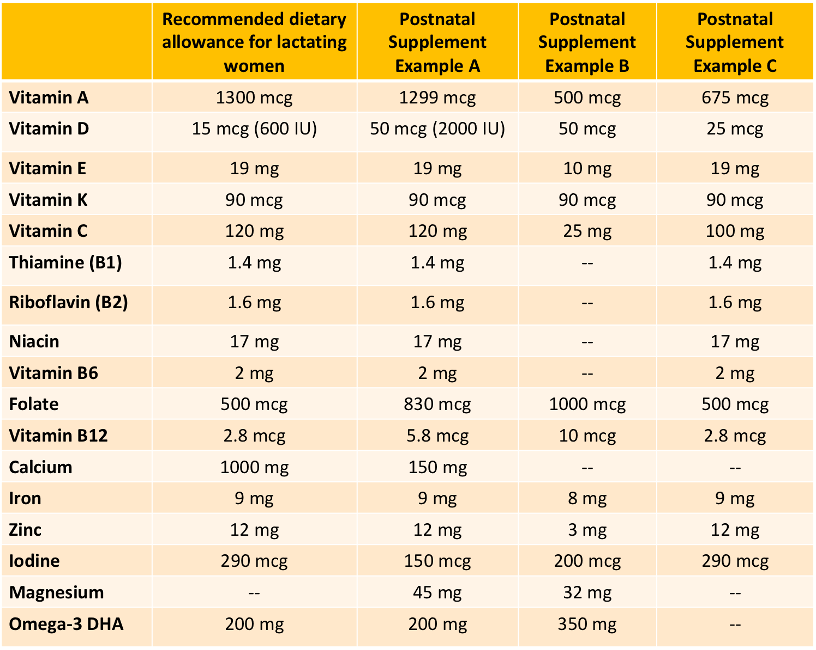

Nutrient requirements for lactating mothers are unique. However, there are large differences between the postnatal supplements that are on the market. When deciding which supplement will be the most helpful for you, it is important to consider one’s own usual diet and needs. If possible, working with a dietitian can help women identify any gaps in their nutrition. The following table shows examples of various nutrient breakdowns of postnatal supplements, as compared to the recommended dietary guidelines outlined above.

Table 1: Formulations of Postnatal Supplements vs. Recommended Dietary Guidelines

Postnatal vs Prenatal Vitamin/Mineral Supplements

Typically, women are told to continue their prenatal supplements during the postpartum period. While this may be appropriate for certain nutrients, it may be inappropriate (providing either too much or too little) for other nutrients. For example, the average prenatal supplement does not provide adequate levels of Vitamins A, E, or C to meet the recommended daily requirements for lactating women and may provide too much iron for a mother whose iron stores have recovered from delivery. The following table shows examples of the nutrient contents of various prenatal and postnatal supplements.

Table 2: Formulations of Various Prenatal Supplements vs. Postnatal Supplements

As evident in Table 2, there is high variability both between the components of prenatal and postnatal supplements and within these groups themselves.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding poses nutritional demands that are distinct from pregnancy. Postnatal supplements may be a good option for breastfeeding mothers to ensure they are obtaining adequate nutrients. There are substantial differences in the contents of prenatal and postnatal supplements. Additionally, although prenatal and postnatal supplements may help fill in the “gaps” in our nutrition, mothers should aim to get the majority of their nutrients from eating a healthy, balanced, and varied diet with plenty of vegetables, whole fruits, whole grains, and healthy proteins.

Each woman’s needs are unique and dependent on her typical diet and health status. If postnatal supplements sound like they may a good option for you, have a conversation with your healthcare provider to consider your unique situation and make an informed decision.

Raina Kishan, MS4

Christine D. Garner, PhD, RD, CLC

References

- “Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin A.” NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 26 Mar. 2021, ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminA-HealthProfessional/.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- “Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin E.” NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 26 Mar. 2021, ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminE-HealthProfessional/.

- Abe SK, Balogun OO, Ota E, Takahashi K, Mori R. Supplementation with multiple micronutrients for breastfeeding women for improving outcomes for the mother and baby. Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2016, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD010647. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010647.pub2. Accessed 01 August 2021

- Hollis BW, Wagner CL, Howard CR, et al. Maternal versus infant vitamin D supplementation during lactation: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):625.

- “Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin C.” NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 26 Mar. 2021, ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/.

- Grizzo FMF, Alarcão ACJ, Dell' Agnolo CM, Pedroso RB, Santos TS, Vissoci JRN, Pinheiro MM, Carvalho MDB, Pelloso SM. How does women's bone health recover after lactation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2020 Mar;31(3):413-427. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05236-8. Epub 2020 Jan 2. PMID: 31897544.

- Bhandal N, Russell R. Intravenous versus oral iron therapy for postpartum anaemia. BJOG. 2006 Nov;113(11):1248-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01062.x. Epub 2006 Sep 27. PMID: 17004982.

- “Recommendation: Folic Acid for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: Preventive Medication: United States Preventive Services Taskforce.” Recommendation: Folic Acid for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: Preventive Medication | United States Preventive Services Taskforce, 10 Jan. 2017, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication#:~:text=Recommendation%20Summary&text=The%20USPSTF%20recommends%20that%20all,800%20%C2%B5g)%20of%20folic%20acid.

- Li, J, Pora, BLR, Dong, K, Hasjim, J. Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid and its bioavailability: A review. Food Sci Nutr. 2021;001-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.2299

- Quinn E, Kuzawa C. A dose–response relationship between fish consumption and human milk DHA content among Filipino women in Cebu City, Philippines. Acta Paediatrica. 2012;101(10):e439-e445. infants?search=Breastfeeding&topicRef=4960&source=see_link#H174264247.

- Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552